The history of Columbia and South Carolina is long, varied and controversial—yet the stories of minority communities often go unnoticed, perpetuating the idea that our city is homogenous when this is not the case.

Many may only consider the emergence of Islam in America from the '90s or early 2000s, but the history of Islam, especially in South Carolina, goes back as far as the Revolutionary War and slavery. A research group at USC aims to not only uncover this history but also celebrate the present-day Muslim community in Columbia.

“There’s a vast scholarship on Muslim Americans, or American Muslims, and much of that scholarship tends to focus on Muslims in the US that are in metropolitan areas in the Northeast, or maybe in the Midwest,” said Dr. Sarah Fatima Waheed, an assistant professor of history and one of the professors leading the Muslim South project. “But [it] largely overlooks the Muslim communities of the Southern United States. And so, we wanted to start to think about the ways that Muslims have contributed to the Southern United States in many, many different ways.”

"I think the reason why people think of Columbia as a lot more homogenous than other cities is because these stories aren't being told," undergraduate senior and principal research assistant Aidan Reilly said. “Since before the United States was even a country, there were Muslims here. So there is this shared history that I think it’s also de-homogenizing Columbia. When people think of the South, they think of a very Christian, very white area, and this is running contrary to that.”

The Muslim South is a project funded by the Humanities Collaborative, which sponsors groups that are researching unique aspects of the humanities, focusing on community collaboration and public outreach. In particular, the Muslim South strives to highlight the experiences of Muslim individuals who live in the American South, starting right here in Columbia.

Waheed explains that her personal motivation for being involved in the Muslim South stemmed from a desire to learn more about the place where she lived.

“As someone who’s a historian, I’m also interested in where I live,” she said. “Having moved here, I am interested in really highlighting stories, especially stories of people that haven’t really been told, they haven’t really been highlighted as much.”

Along with Waheed, other contributors to the project include Noah Gardiner, assistant professor of religious studies; Jessica Barnes, associate professor of geography; Carl Dahlman, director of the Walker Institute of International and Area Studies; and several graduate and undergraduate students. Together, these individuals hope to both obtain oral histories from Muslims in Columbia while also collaborating on community-based events.

“Historically, American universities have been very exclusive in terms of what they give and interact to the community,” Reilly said. “So there's definitely a gap between the knowledge that’s accessible to the community that the university holds. And so, we’re very much trying to bridge that gap but also bring the Muslim communities together in a larger way through this shared history that Muslims have in the South.”

Waheed echoed this sentiment. “That’s something that I’ve noticed is that we just don't have people's stories. The problem with that is that when you don’t tell your story or when it’s not recorded, then someone else can tell your story for you. So one of the aspects of this project is to really get people from the community involved and have them tell their stories.”

The Muslim South’s first launch event, hosted on Oct. 9, 2024, featured a seminar by community liaison and Director of FoodShare Omme-Salma Rahemtullah. During this seminar, Rahemtullah talked about the intersection of East Africa, South Asia and Islam in the present-day American South, with a special focus on the Ismaili community in South Carolina. Rahemtullah explained that the oldest jamatkhana, or place of worship, in the US was actually established in Spartanburg, SC by Ugandan South Asian refugees. The event also included East African and Asian food made by a community member.

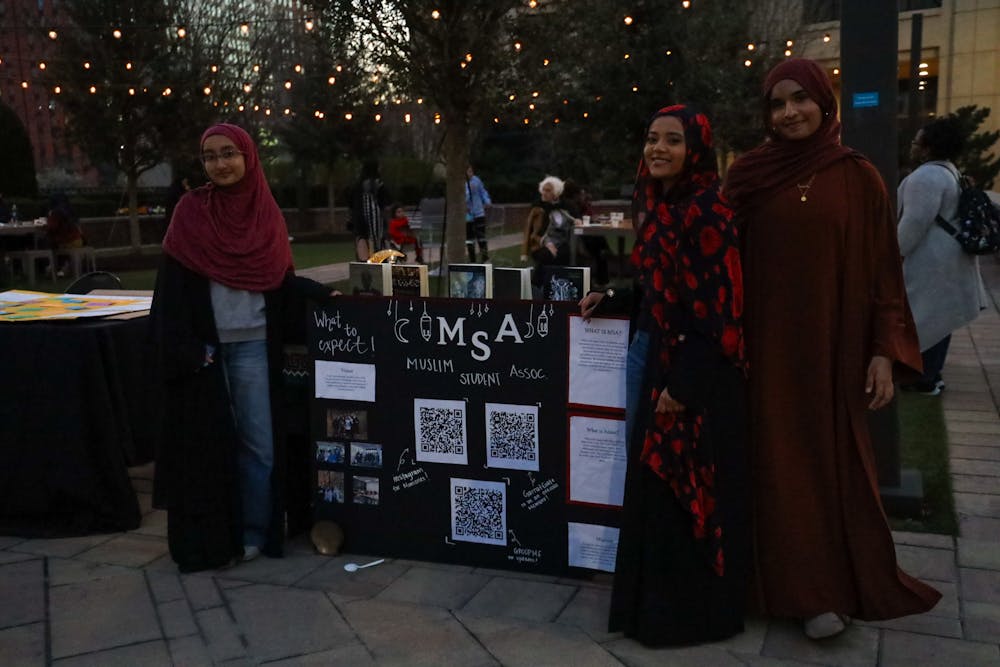

On March 6, 2025, The Muslim South also collaborated with the Columbia Museum of Art, Columbia Muslim Association, and various community members to host Columbia’s first-ever Ramadan Night Market, which included arts and crafts, Mediterranean food, clothes, henna, and more. Scheduled during Ramadan, the Islamic holy month where Muslims fast from sunrise to sunset, this event was intended to show how night markets in Muslim-majority countries come alive during this month while providing an opportunity for individuals to learn more about Ramadan and foster community.

“This is an opportunity for people to not just be exposed to the religious aspects of this holy month, but also see the cultural aspects,” Waheed said.

While these community events are essential, the Muslim South’s goal also includes recording history and the lived experience of individuals in Columbia. The project hopes to create a larger repository of Muslim lived experiences and stories available for access in both the South Caroliniana Library and SC State Museum Archives—starting with the oldest Muslim community in South Carolina, African American Muslims.

“While we don’t know the exact numbers, the earliest Muslims in the United States were enslaved Africans,” Waheed said. The Lowcountry Digital History Initiative explains that about 15 to 30 percent of enslaved individuals came from Muslim-majority regions, such as Senegal, Mali, Guinea, Sierra Leone and Gambia and often entered the colonies through Charleston, SC. In fact, Omar bin Said, who was initially brought to Charleston, wrote one of the only known autobiographies authored by an enslaved individual in Arabic.

Sharing this information is vital as it sheds light on the diversity of culture and religion among enslaved individuals as well as the lesser-known history of Muslims in the United States. “I think for a lot of Americans, Muslims popped up in the mind after 9/11,” Reilly said. “But this shows them that people have been here.”

So far, the Muslim South has completed two oral histories of community members of Columbia’s oldest mosque, Masjid As-Salaam: Imam Omar Shaheed, who has been active in interfaith dialogue in both a local and international context as he has previously traveled to Jerusalem for an interfaith conference, and Mary Hamin, the oldest member of Masjid As-Salaam.

“It’s been really a privilege and an honor to hear the story of Imam Omar Shaheed of Masjid As-Salaam and to interact with the community there at that masjid to learn about their experiences of being Black and Muslim in the South,” Waheed said.

Just as important are the experiences of Muslim communities that have recently formed in Columbia. Sahifa Sadiq, a sophomore undergraduate research assistant, is planning to document the oral histories of the Rohingya group in Columbia.

“I know the language firsthand, and they’re one of the newer refugee groups residing here in South Carolina, so that brings a different perspective into the whole picture,” Sadiq said.

Sadiq explained her motivation for being involved in the Muslim South. “A lot of me joining came from my own background,” Sadiq said. “I’m from Burma, and I’m ethnically part of the Rohingya group, and they are persecuted in Burma for their ethnicity and their religion.”

She quickly found her passion while working for Dr. Waheed and the project. “When she offered me a research position role, I felt like it wasn’t just something I was doing,” she said. “It had meaning, it had passion, and I really fell for the work.”

Sadiq expanded on this by emphasizing the importance of spotlighting lesser-known Muslim communities.

“It’s really important to bring light onto things you don’t hear of, particularly in the South,” Sadiq said. “There’s so many groups, so much culture, so much language that just gets hidden, within media, within everything—there’s just not a lot of light into it. So I just think that being involved here pushed me to push for the people that are not spoken about. Because growing up, my entire life I had never heard someone pushing to speak for my people or the ethnic groups that are unheard of.”

Waheed explained that this project is just starting to gain momentum, and they look forward to continuing to both foster community and preserve the unique history of Columbia and Muslim voices.

“One of the things that I think that’s important for people to take away from this is that this is an opportunity for anyone, really, to learn more about the people who live here—all the different kinds of people who live here—and to learn from their own, right? To interact with people, but to also hear their stories,” she said.