At the start of the 20th century, Columbia was a promising city. It was a textile manufacturing hub. It already housed the University of South Carolina, Allen University, Benedict College and Columbia Female College. There was a sense of optimism in urban life. All over the country, people left the countryside to work in urban factories or mills.

It was not all that promising, though. American cities as we know them today are the result of decades of residential segregation, and Columbia is no exception.

Columbia was a crowded and dirty city. The Great Depression hit hard, and discriminatory social conditions called Jim Crow laws set racial segregation in stone. As it always was, white people were worthy of space, and Black people were not.

Dr. Bobby Donaldson is a UofSC history professor and the USC Center for Civil Rights History executive director. He researches the history of Black neighborhoods, among many other topics. According to Dr. Donaldson, the heart of Columbia as we know it was home to disenfranchised minority communities up until the past 40 years. The people who lived there faced rundown and crowded conditions with poor sanitation.

Wheeler Hill, located near Bates and the Campus Village, was one of these communities. Once a lively and close-knit neighborhood, now only about a hundred homes remain, UofSC graduate Sophie Kahler discusses in "Wheeler Hill." It was a "self-sufficient and proud community."

Kahler describes these neighborhoods as "overcrowded with deteriorating housing and lack[ing] infrastructures like indoor plumbing, electricity, paved streets, sidewalks, and garbage collection" in "The Evolution of Columbia's neighborhoods".

Still, city developers saw economic potential in Wheeler Hill and other working-class Black neighborhoods. The City Beautiful movement swept the US to enhance the "aesthetic environment of its many inhabitants," writes the New York Preservation Project.

In "The Evolution of Columbia's Neighborhoods", Kahler states that "trends of urban development and racial segregation," such as urban renewal, redlining and racial zoning, "manifest in Columbia's neighborhoods and contribute to larger racial inequalities."

Urban renewal was a national movement to rid cities of sums and beautify cities. The city of Columbia, University of South Carolina, Columbia Housing Authority and federal government ran with this. They planned to spruce up the city and were largely successful. Since the mid-20th century and into the 2000s, Columbia has seen improved roads, landscaping and attractions, like shops and museums.

Almost everyone believed urban renewal was for the public good. A flourishing city is clean. It has exceptional schools and homes with manicured yards—but at what expense?

To make room for a profitable and aesthetic city, they had to eliminate Black neighborhoods. Thus, redlining was born.

Redlining is "a discriminatory practice that puts services (financial and otherwise) out of reach for residents of certain areas based on race or ethnicity." Under the New Deal, the Home Owner's Loan Corporation (HOLC) intended to aid homeowner's on their mortgages and foreclosures. They made it clear that a flourishing city is a white city.

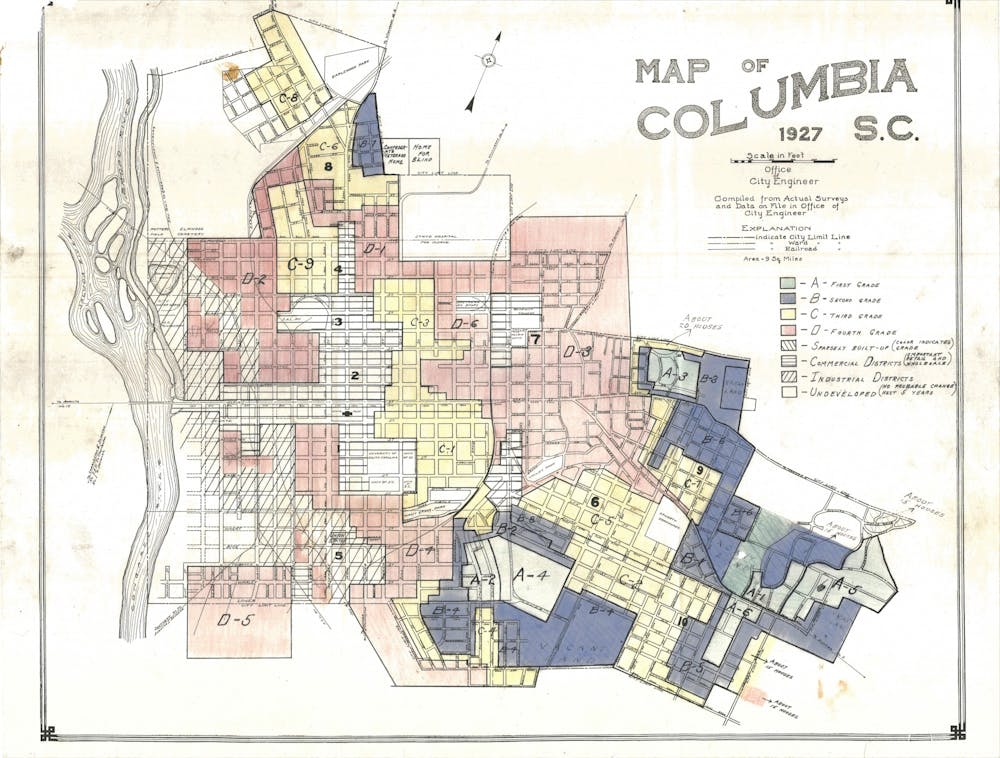

Although redlining is illegal, that didn't stop developers. In 1927, the HOLC created a map that ranked neighborhoods from A-grade to D-grade based on their appeal to investors and homeowners. Disenfranchised neighborhoods were labeled D-grade, purposely singling out the Black inner-city communities. These neighborhoods' estimated income ranged from $200-$10,000. Lenders intentionally gave less to minorities. Naturally, the wealth divide between white and Black Americans grew.

Columbia soon followed the national pattern of "white flight." White residents moved away from urban Columbia and into neighborhoods, sparking the growth of suburbs that today we recognize as Forest Hills and Shandon. To make matters even worse, the Federal Housing Administration strictly urged employees only to insure home mortgages in white neighborhoods.

Title I of the 1949 Federal Housing Act funded the local Columbia government development. "The victims, those who ultimately suffer in that process are poor, working-class Black and brown people," says Dr. Donaldson.

Dr. Donaldson asserted, "There was no way the University of South Carolina could have grown to the south and to the west without eminent domain and the acquisition of those properties." Eminent domain allowed the local government to seize private property for the public good. Columbia developers demolished the inner city, as they perceived the people who lived there as threatening to the "social, moral and economic health of the entire city," Kahler wrote. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the local government destroyed 600,000 housing units.

Activists fought to preserve Black-owned spaces. UofSC bought the historic Booker T. Washington High School in 1974, which has educated Wheeler Hill and Ward One's youth since 1916. The University demolished the main building and transformed another into the Booker T. Washington Auditorium. Students and their families protested the sale in favor of preserving Black-owned spaces under federal slum clearing programs. Meanwhile, UofSC was building white educational facilities in their place. Black inhabitants had no part in the "greater good" of Columbia.

While some struggled to maintain the pillars of their communities, Columbia developers began the "fight blight" movement. Bloomberg describes blight as "a disease that threatened to turn healthy areas into slums." In 1951 and 1964, the National Civic League even granted Columbia the All-America City Award, which honors cities that promote "inclusiveness and innovation to successfully address local issues."

The University of South Carolina, the City of Columbia, the Columbia Housing Authority and the federal government justified this urban renewal effort with a "compelling case," Dr. Donaldson expressed. The economy would improve and taxpayers would be satisfied. After all, they created student housing, educational buildings, and arenas.

Before this expansion, which primarily took place in the early 1970s-1980s, Blossom and Sumter St. were UofSC's boundaries, says Dr. Donaldson.

UofSC continued growing after the eagerness for urban renewal finally died down in the 1970s. The university acquired and destroyed Black homes, Black churches, and Black businesses. Ward One stood in place of our iconic UofSC attractions. If you live in the Greek Village, work out at Strom or attend shows at the Koger Center, you've walked the same grounds the city and university once deemed slums.

Ironically, the University most recently took its most significant growth to what was once the center of Wheeler Hill. In place of the disenfranchised community, modern high rises house thousands of students. UofSC calls this project the Campus Village. The UofSC Facilities Department wrote, "The project's design, while contemporary, was planned in collaboration with adjacent neighborhood groups and will adhere to existing community and university aesthetics."

Most displaced families resettled in the north Main St. area and beyond Williams Bryce Stadium. Remnants of black neighborhoods exist in what Dr. Donaldson calls "the direct shadow" of the campus. St. James AME Church on Henderson still operates. Another Black school building in the area called the Benson School remains but is now owned by the university.

"It is a tragedy that has been repeated in nearly every major city in this country, where a core downtown community had lived, thrived, and then business people, education leaders, elected officials then decide that for the betterment of the community, we're going to move into these properties," says Dr. Donaldson.

"What I've tried to make the case to the university leadership is that you will build these buildings, but at least acknowledge where they are, and tell the context of the history," says Dr. Donaldson. UofSC students deserve to know the history of Columbia and their school, even if it doesn't paint them in a positive light.