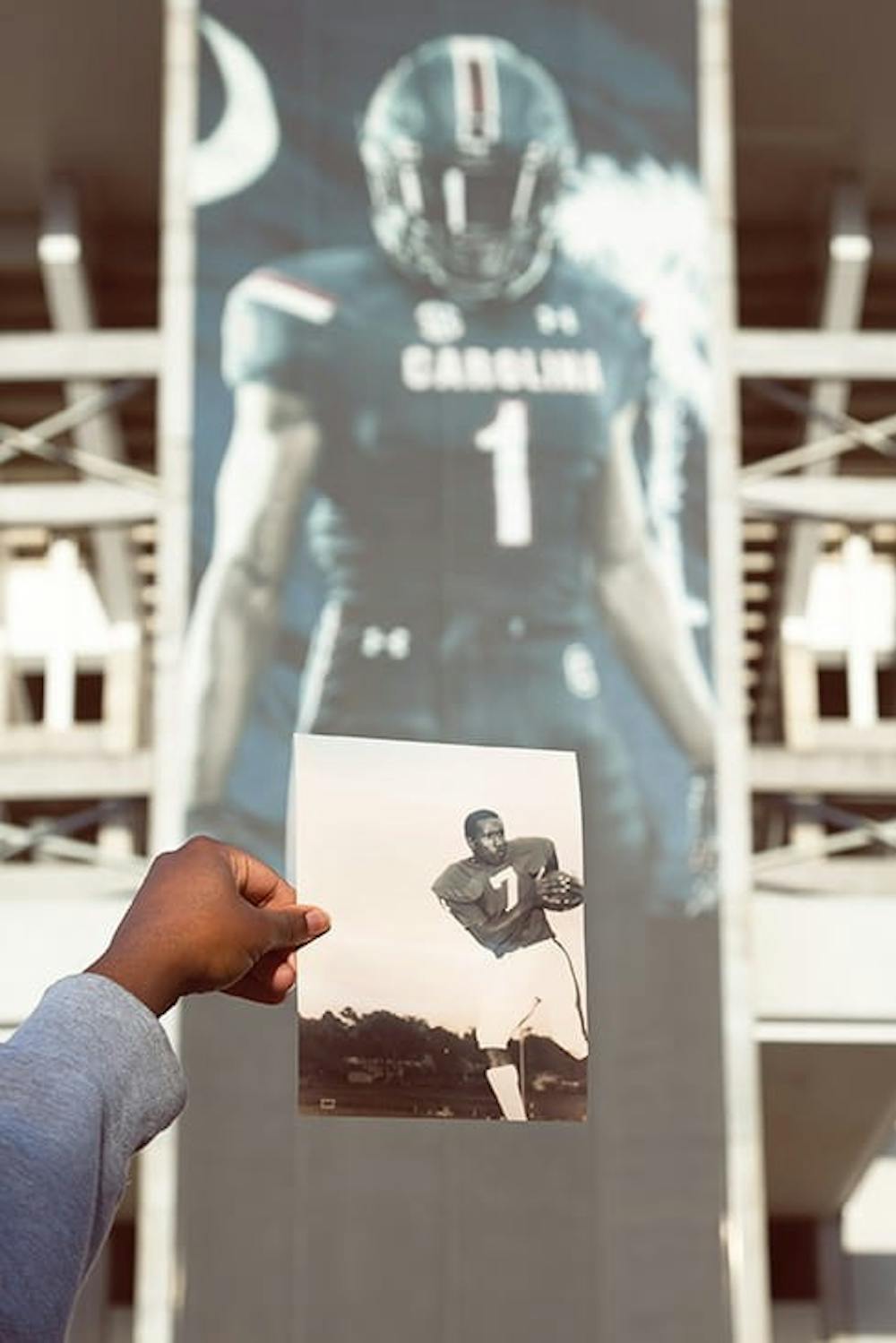

Photo by Zhané Bradley.

I sit here staring at a blank document, a daunting task before me. To write a story honoring a man I have never met, never held a conversation with, never even seen in the flesh, yet has had a strong impact on my life: Ansel “Jackie” Brown, my grandfather. He left this world at the hands of liver cancer well before I was even thought of, leaving me here to piece together his life and legacy. Because of this, he has always been like the star of a folktale in my life. I was always hearing about the funny, witty, and thrilling things he would do. I can recall visiting distant family and family friends in Jonesville, NC, where my grandfather called home, and constantly having my last name switched out for “Jackie’s grandbaby.” Whenever his name was mentioned I could see the all-but-subtle changes in people’s facial expressions from mundane to awestruck as they drew mental connections from me to my grandfather.

So what was so grand about my grandfather? Why did his name bear so much weight in his hometown? Why am I writing about him today? And why does any of this concern you? Well, as a student, a faculty member, a fan or an admirer of The University of South Carolina, you too have been impacted by my grandfather’s legacy. If you’ve ever gone to Williams-Brice Stadium on a sweltering hot Columbia afternoon to cheer on Gamecock football, then you’ve felt his impact. If you’ve ever camped around a TV to watch your favorite Carolina ball players, then you’ve felt his impact. If you’ve ever heard of UofSC-made NFL stars like Jadaveon Clowney, Alshon Jefferey and George Rogers, then you’ve felt his impact. If you’ve ever tried to maneuver the streets of downtown Columbia on a Saturday of a home game, then you’ve definitely felt his impact. Jackie Brown, alongside other notable men, helped create the present-day craze of Carolina football.

My grandfather, Jackie Brown, was the first African-American to letter-in and start for the varsity football team in the spring of 1970. Before him, only one other African-American had ever been enrolled on a football scholarship at the University of South Carolina — Carlton Haywood in the fall of 1969. While Haywood was the first black student to be recruited for Carolina football, he redshirted in 1970 and eventually earned his varsity letter in 1971. My grandfather arrived on campus in the fall of 1969 on a baseball scholarship (also integrating the baseball team) after turning down a contract to play professional baseball for the Cincinnati Reds straight out of high school. That following spring, in the midst of baseball season, he was approached by a representative of the football team and asked to try out.

Having recently suffered a hamstring injury that put him behind in baseball, he took the offer and tried out. Less than a week later, he earned a spot on the team as a receiver with a full scholarship. From that moment on, my grandfather skyrocketed. He was a recurring starter and varsity letterman in 1970, 1971 and 1972. By his senior year, he was one of the top 50 prospects in the nation and was picked up by the Baltimore Colts but suffered another severe hamstring injury that led to him being released. However, he almost immediately received another three-year contract that was more alluring than that of the Colts from the Redskins that same year. He ultimately turned down the contract to go into Christian ministry. Along with baseball and football, my grandfather also played on the junior varsity basketball team alongside Casey Manning, who was the first African-American basketball player at USC in the fall of 1969 and is now a circuit court judge for the Fifth Judicial Circuit.

My grandfather accomplished so much within his first four years at USC and he went on to achieve even more in his 40 years of life. He led a life of love and peacefulness. Even in the face of prejudices and micro-aggressions he remained true to his “do unto others as you would have them do unto you” Christian roots. I was able to get in contact with Carlton Haywood and Casey Manning, who were dear friends to my grandfather, and they both described him as a just, level headed and “spirit-filled” man. In a cassette tape recording my dad had safely stored away among many other personal items and mementos of his father, my grandfather tells his life testimony to an audience of fellow pastors and clergymen. He speaks a lot on his personal relationships, his spiritual journey and his time leading up to and being at USC. Listening to him speak on this hour plus long tape gave a surreal glimpse into the gentle nature of my granddad. I couldn’t go without noticing the humility of his heart and the genuineness of his character. He was a man blessed with many talents, yet his heart’s desire was so simple: to love God and to love others. My dad told me that one of the most impactful things his father would say to him growing up was, “always give your best and put God first.” As my father’s child, I can attest that this sentiment has proven itself solid in my father’s life and now in my own. It is not hard to see why my grandfather excelled so much in life. Not only was he extraordinarily talented and hardworking, but his magnetizing compassion for others drew people in. I have similarly found myself being drawn in deeper and deeper as I continue to dig not only into the history of my family lineage but also of my future alma mater.

While reflecting on the past and their connections to my grandfather, Mr. Manning and Mr. Haywood painted a picture of the strong bond among the three of them that went beyond that of athletic affiliation and even of friendship. They had created a brotherhood with each other. They played beside one another, they did life together, they faced injustices together and they created lifelong memories together. Being the only three African American athletes in the entire athletics department at that time, they experienced the world in a way that only they could relate to. Although these three pioneers faced challenges such as finding a teammate willing to room with “the black guy”, or coaching staff being insensitive to their cultural expression, or even having teammates intentionally cause them physical harm; their love for their sports outweighed the pressures that come with being any kind of pioneer. As the great Condoleeza Rice once said, “People who end up as ‘first’ don’t actually set out to be first. They set out to do something they love.” These guys persevered through multitudes of covert micro-aggressions and scattered incidents of overt discrimination for the love of the game.

So, here I am, 50 years after my grandfather was on this very campus. Walking the same paths he walked, going to the same buildings he went to, sitting in the same stadium he played in, and continuing the legacy he started here at UofSC. I find it no coincidence that I am here in his absence: not only in his absence physically from Earth but also in the absence of remembrance of his legacy and the legacies of peers like Judge Casey Manning and Mr. Carlton Haywood. This article is much too short to give full justice and pay homage to these trailblazers and their bravery to pioneer in uncharted waters on this campus. Their willingness to be the first has paved the way for so many little black boys who dream of playing ball in Williams-Brice Stadium or Colonial Life Arena to have their dreams fulfilled. This school’s athletic department profits millions each year off of the work of many talented and driven young black men who love the game just as my grandfather did. They give their all on those practice fields, in the weight rooms, in their classrooms and in our beloved Willy-B stadium. My grandfather didn’t live to see the current impact of his decision to turn down a professional baseball contract to play sports at this University, so I take full responsibility to pay him respect for all of his efforts. They did not go unnoticed or in vain. Although I have never once laid eyes on my grandfather in the flesh, Ansel “Jackie” Eugene Brown will always be a jewel in my eyes and in my heart. The connection I feel to him being here on this campus is almost palpable. I can only hope to honor his memory and continue the legacy of love, hard work, dedication and perseverance that he started here in 1969.