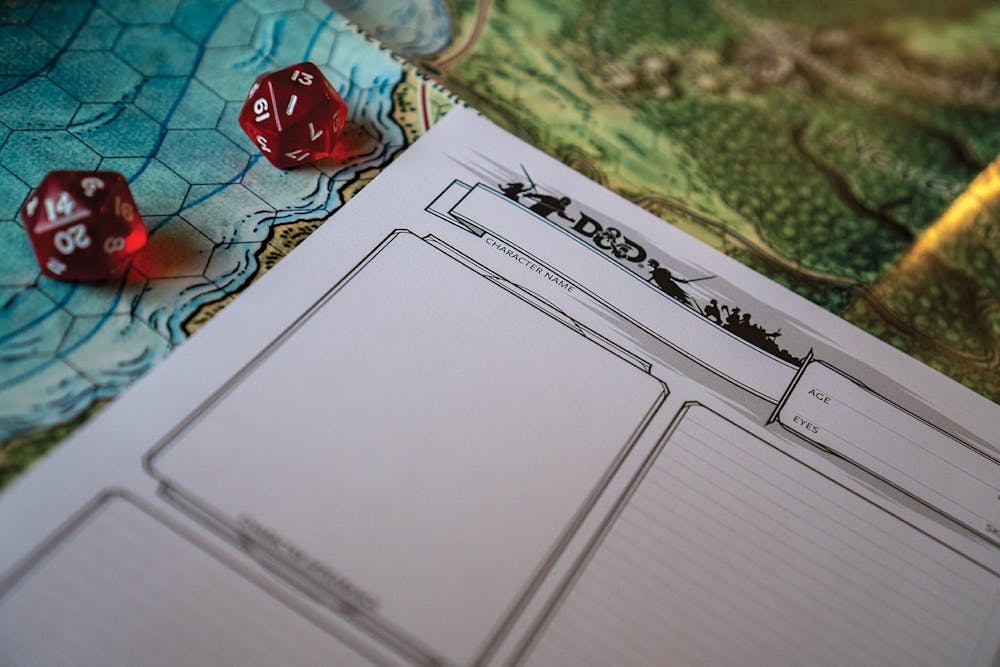

Photo by Alex Wyatt.

A basic’s dictionary for D&D terminology

campaign. n. all sessions taking place in the same world with more or less the same set of characters on a specific mission or missions.

DM/GM. n. Dungeon Master or Game Master.

metagaming. v. using knowledge gained outside of gameplay to influence what a character does.

nat 20. n. a critical hit or an auto-success; the highest number one can roll on a 20-sided die (d20). See also: nat 1; auto-failure.

one-shot. n. a campaign that can be completed in one session with no further expansion.

retcon. v. as the GM, to retroactively alter past events or facts previously established in game.

session. n. one discrete scheduled period of play.

PC. abbrev. player character. See also: NPC, or non-player character (controlled by the GM)

Before we begin—the name Dungeons & Dragons, or D&D, operates linguistically like “Jell-O” or “Band-Aid.” It stands in for the entire category of objects: gelatin dessert, adhesive bandage or tabletop roleplaying games. In reality, hundreds of different systems exist, each requiring different types of dice-rolling and math. I’ll be using D&D as a stand-in for all systems throughout this article (and it will be formatted, in my opinion, as the much more aesthetically pleasing D&D rather than, as some people spell it, DnD).

So now that we understand the referent—what is D&D?

Trying to answer this question in 1000 words or less feels like an exercise in futility; it’s like asking “what is football?” or “how do memes work?” No flat explanation of the rules will come close to teaching as easily as watching, and no insiders jargon will make sense without experiencing it yourself.

The one consistent element for D&D campaigns—whether they involve low-magic or crystals and wizards around every corner, whether they take place in 15th century Europe or Mars or Billings, Montana—is that the game is created from the combined efforts of the players and the GM. The GM creates the world, and the players make choices within it.

The difficulty ranges, not based on age, but with comfort in exuberance and risk-taking; little kids can easily play if they possess a modicum of self-confidence. Several of the most acclaimed DMs recommend improv classes, since D&D can be seen as an elongated “yes, and.”

Jeff Arling, a senior computer science major here at UofSC, likens RPGs to any broader category of entertainment.

“A game can be any genre, with any balance of seriousness and silliness, with any general level of commitment. It’s like: who likes to watch TV? Pretty much anyone, depending on the show.”

“My favorite campaign was our first Call of Cthulu,” said Emily Sellers, a senior biochemistry major. “It took place in the 1920s; our group consisted of detectives, a private eye, and a mob boss. For me, we just started our most interesting campaign yet—D&D 5e where everyone is an awakened cat. We live in an old wizard’s tower and she feeds us treats when we complete quests!”

Sellers has been active as a GM in the past. “I love storytelling, and GMing is just a different format beyond a novel or poem. I love to come up with puzzles for the players to solve or put them in difficult situations—GMing is a cool way to learn how different people think.”

Arling also GMs, using a system called 7th Sea (2e); planning a session can take anywhere from ten hours to thirty minutes, depending on how fleshed out he wants the world to be.

“Starting out, I tried to plan out every detail, almost like a choose your own adventure book or a video game, where there are a finite number of paths—but that usually either turns into chaos when players do something you don’t expect or into railroading when the players feel as though they can’t have agency.

“Now, I put most of my effort into developing the world at large and the characters within it… That way, I can do a lot of writing, which I enjoy, and I have a lot of material to pull from when players do something I wouldn’t have predicted. But it doesn’t always work—and I’ve learned not to take it too seriously when things get a little silly or off-track.”

The learning curve can feel daunting for new players (especially those dragged into it by a significant other or overeager friend). Unlike TV or movies, D&D requires a non-passive participant; unlike video games, the participant, in one way or another, is you. Your dialogue, your choices, your imagination building out the world around you. It can be overwhelming on all fronts.

“I know that a lot of what scares off people from DnD type games is the level of commitment—agreeing to do something regularly that takes hours,” Arling said. “Something that people don’t really understand is that…a 'campaign' can be three games over 5 months, and one-off stories with throwaway characters can often be a lot of fun.”

“No matter what interests you have, none are too niche for RPGing,” Sellers said. “You can make absolutely any world, character, or situation specific to you.”

Many proponents of D&D will expound on how improv strengthens self-esteem, how accomplishing a goal with friends increases closeness and collaboration; how, at the end of the day, heroes and monsters matter less than the story you’re building together. All those grand sentiments do exist—but D&D is just as much about making stupid inside jokes with your friends and completely wrecking the planned storyline.

The time was ripe for a D&D revival amid the youths. After all, the age of cool disaffectedness has passed (and good riddance, I say). Our generation is the generation of finding it super cool and sexy to genuinely, vulnerably, publicly care about things.