What you know about the Honors College depends entirely on who you are. If you’re an Honors Ambassador, tasked with recruiting the incoming freshman class, your conversations overflow with information about the tight-knit community, the teacher-student ratio, the successes of alumni in dozens of fields. If you’re a Capstone student, you roll your eyes at the group of Honors students talking loudly on the Horseshoe about the excruciating 10-minute walk from the Honors dorm to the free printing lab in Harper-Elliott. And if you’re minding your business as an everyman student at USC, you might not think about the Honors College much at all, as busy as you are with your own demanding classes.

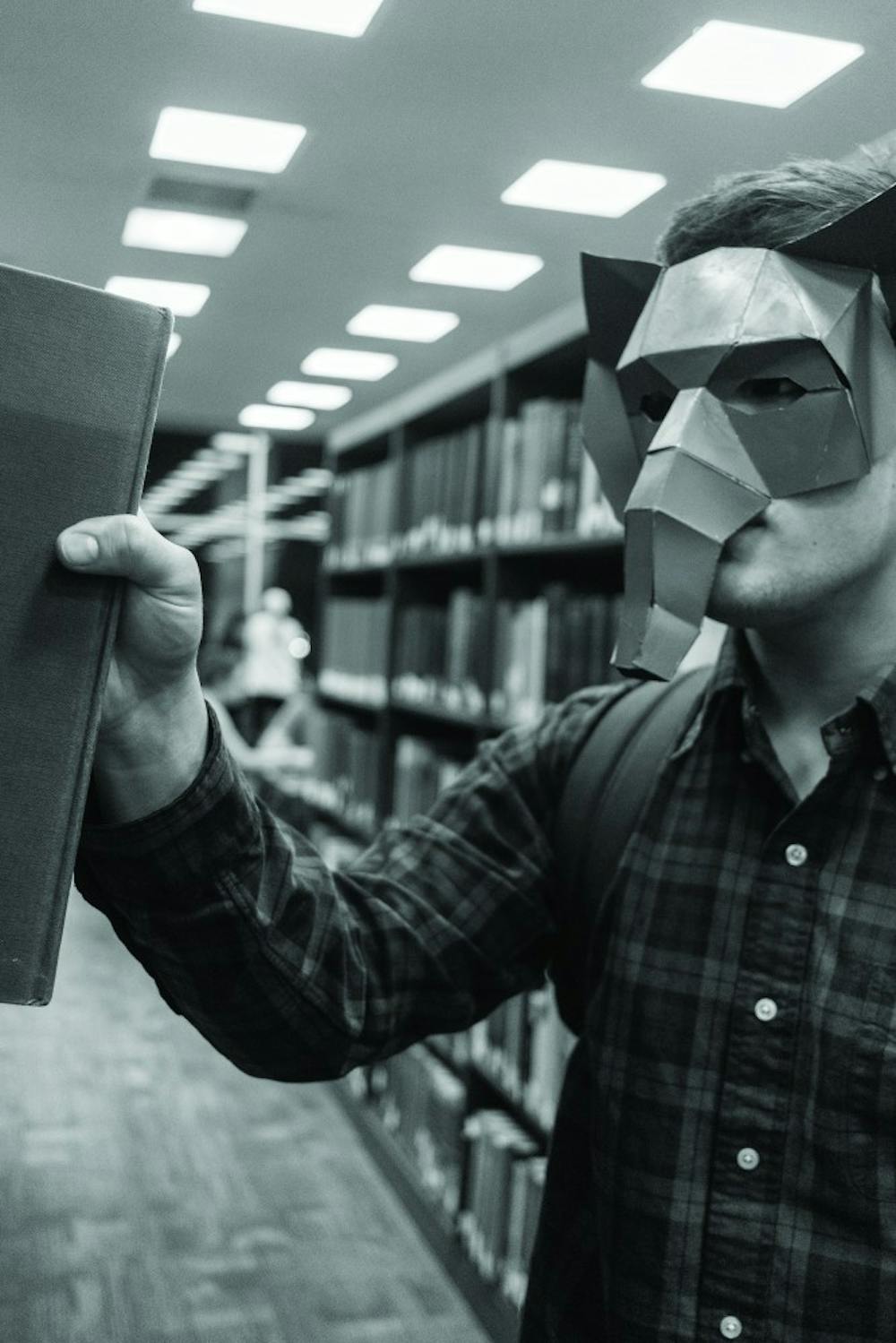

Like the elephant approached by six blind men, the Honors College feels different in the hands of each student. And like the men, each holding the tail, the ear, or the trunk, each student thinks they have the right impression of the Honors College. In reality, the Honors College encompasses both the best part of academia — intellectual growth, interdisciplinary work and peer-to-peer relationships — and the worst, which sometimes manifests as blatant egotism and elitism.

“My friends in the Honors College are brilliant, but I would never have known they were in the Honors College until they told me,” said a senior public health major. “The Honors College people that get on my nerves — it’s like their identity. They’ll walk up to you and say, “Hi, I’m so-and-so, I’m in the Honors College.” They think they’re God’s gift to the world.”

This seems to be the biggest misstep in Honors and non-Honors relations — non-Honors students continually get the vibe that Honors students think they’re smarter, harder-working and generally better. The perception exists within the Honors College, too.

“I always feel like I’m cool, I’m fine, but I have class with people I want to strangle,” said a senior English major in the Honors College.

Others felt like the forced community of the Honors dorm contributed to the formation of friend groups that some would call tight-knit, and others would call exclusionary.

“I have not met anyone in the Honors College who was easy to approach,” said an Honors freshman IB major who lives outside of the dorm. “It’s hard to make groups in class because everyone’s friends are from their hall."

Dozens more students harbor similar opinions — not necessarily because of the Honors College itself but the type of students it attracts, who tend toward “narcissism and self-importance.” This echoes an ongoing debate in the field of education: Should gifted and talented children be separated from the larger group for their own betterment or does this lead to low emotional intelligence and weak interpersonal skills?

The concept of an Honors College at USC began in the early 1960s, when a select group of faculty scattered across different departments noticed that South Carolina’s most promising students were leaking past our state borders, pursuing degrees at universities like Duke, Vanderbilt and Emory. In order to combat this, an Honors program was started, the eventual goal of which was to not only retain students who were moving out-of-state, but attract high-achieving students from other parts of the country.

“From the beginning, [the professors] knew they were doing something remarkable,” Dean Steve Lynn said. “I was part of the small original program, which was just a few classes and a very small group of students at the time. But the faculty in charge kept asking for more funding, more structure and, surprisingly, they kept getting what they asked for.”

Fast forward to 2018, and the South Carolina Honor College retains the ranking of the No. 1 public honors college in the country. Its students regularly win national fellowships, its living-and-learning community centered on an exclusive dorm has garnered attention from higher education programs nationwide, and the student-teacher classroom ratio has stayed steady at about 15:1, even in an era when more students are attending college than ever before.

But even as the Honors College expands its reach — another wing of the dorm is set to begin construction sometime in 2018 — in some sense, this has driven the divide between the Honors College and the rest of USC.

“The only time I interacted with Honors College students at orientation was at the Koger Center; at the end of the meeting, certain orientation leaders put up signs saying ‘Honors College students, this way.’ They all stood up and left as we sat there like, ‘Haha, guess we’re stupider than them.’” This is Eugene

Suydam, a sophomore economics major who transferred into the Honors College last year. Suydam knew that he wanted to transfer into the Honors College from his first day on campus. You pretty much have to know — otherwise, your Carolina Core requirements will have to be repeated within the Honors College.

“I walked into my first advising appointment freshman year and said, ‘Hey, I know I want to transfer, so please don’t let me take unnecessary classes. I want to graduate in four years.’” Suydam also focused his attention on keeping his GPA high and involving himself on campus. He joined student government and Garnet Circle (a networking organization based in the Alumni Association) and stepped out of his comfort zone by trying groups like OverReactors Improv.

“As long as they see that you’re engaged with the community, that you can make connections with your professors and value the intellectual development that’s encouraged in the Honors College, it’s fairly easy to transfer in from regular USC. Much easier than getting in out of high school,” Suydam said.

Another option for non-Honors students looking to take advantage of the programs offered is to engage with the professors directly. Many professors teaching Honors classes will accept non-Honors students into their classes, provided that they express their academic integrity, their interest in the subject matter and their willingness to go the extra mile.

“My professor freshman year had students write a letter on why they wanted to take the class if the class wasn’t full,” said Casey, an experimental psychology major in the Honors College. “Honestly, it worked out for the best — some non-Honors students end up way more driven than Honors College students because they have to work harder to make connections with professors and make the grades.”

Every organization on campus has the risks and benefits of being misrepresented by its members. And though there is a screening process — the holistic and nebulous procedure of applying to college — in the end, the members of the Honors College can only be vetted so much.

“I think the most important trait we look for in Honors students is intellectual curiosity,” Dean Lynn said. “That doesn’t mean that non-Honors students can’t get a fantastic education at USC, or that they’ll be any less successful.”

So before you get frustrated with motormouth Honors students — or, Honors students, before you isolate yourself from the rest of USC — take a minute to consider another perspective. Reach out, extend your arms, and move away from the part of the elephant you’ve been feeling. Who knows? You might find something totally new.