Let me start by saying that I am woefully underqualified to write this article.

I grew up in a small town in the Corridor of Shame, two blocks from the public elementary school. I used to swing and seesaw on the plastic playground that belonged to the local district — until I started going to kindergarten at the local private academy. I’ve never dealt with a lack of classroom resources or an insufficient teacher-to-student ratio. And most importantly, because I am white, I have always seen my culture and race affirmed in my history texts, the novels I read, and on the walls and bookshelves of each classroom.

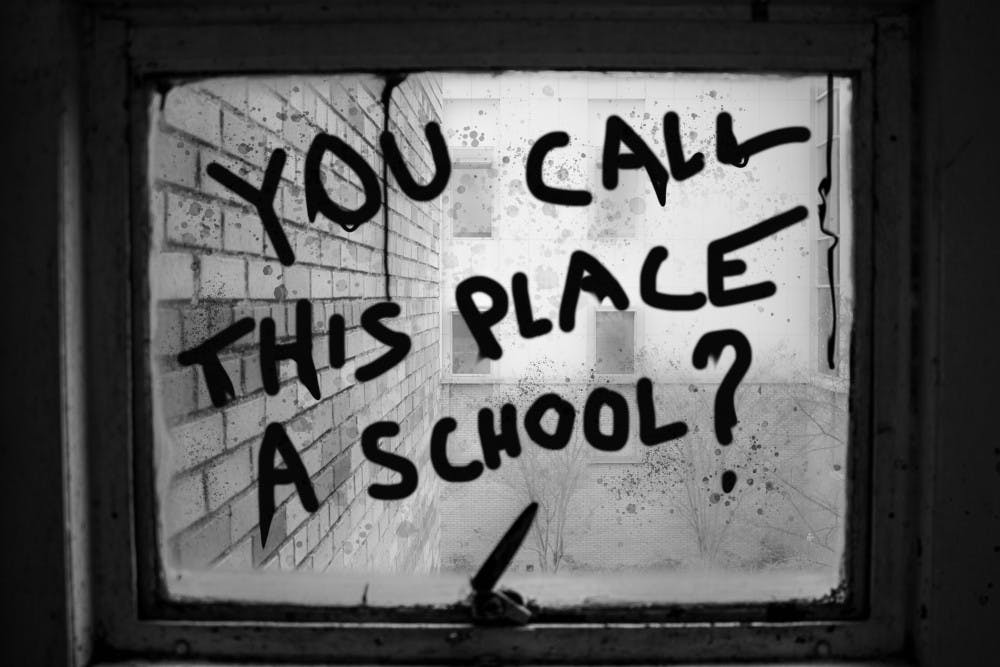

Across the state of South Carolina, even those basic requirements for a quality education have been scarce for decades. We’ve never been known for our stellar public school system, but in 2017, South Carolina’s public schools officially were ranked 50th in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. The Post & Courier called it “another low to South Carolina’s lackluster reputation on schools.” Many educators would call that an understatement.

The Corridor of Shame became the face of South Carolina’s educational crisis in 2006, when a documentary was filmed onsite in dilapidated classrooms with ancient desks. It focused on the collapse of order and learning in rural schools. On Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign, he made a stop in Dillon, South Carolina to speak at one of the featured schools. A decade later, the schools haven’t seen much improvement, despite new attention.

“There’s a lot of reasons that rural schools suffer,” said Jessie Heinrich, a senior student-teacher who plans to move back to her hometown of Baltimore after graduation. “First, the teachers themselves are overworked and underpaid. It’s an incredibly taxing job, and the budget with which they have to pay you is almost insulting to someone not from the area. You’re also not getting a huge influx of teachers, especially if they grew up somewhere metropolitan — it’s really hard to get someone to move to a rural area when they’re used to an urban one. There’s a lot of teacher burnout — there’s a program where you can pay off your student loans if you teach in an impoverished area for a certain number of years, but that doesn’t help establish teachers in a school for the long term.”

The University of South Carolina, to its credit, has done its best to distance itself from a statewide reputation of poor academic performance. Even though less than a third of South Carolina eighth graders scored “at or above proficient” in core subjects like math and reading, most USC students enter with a weighted GPA of above 4.0 — mostly As and Bs, in other words. Additionally, although the average range on the ACT for admittance into the USC class of 2016 was 25-30, South Carolina’s average ACT score was 19 — a data point which has particular significance, since South Carolina is one of few states to require every high school junior to take this standardized test.

My central line of question going into this article revolved around whether the university had any responsibility for improving the state school districts. After all, USC advertises as the flagship public university of our state. It stands to reason that the administration should be looking to serve the public school system, which in turn should be ideally set up to prepare students for the rigors of academics at USC.

But I knew even before I began that racial inequality would turn out to be the real topic of research. USC’s class profile has never been stellar in terms of African American admittance — 10 percent of the Columbia campus population is black, and 15 percent across all USC branches. And yet across South Carolina K-12 public schools, black enrollment accounts for 36 percent of student populations.

“Our overarching goal is to see all children achieve — but specifically African American children rarely see their full potential realized in our state’s and nation’s schools,” said Dr. Gloria Boutte, Founder and Executive Director of USC’s Center for the Education and Equity of African American Students (CEEAAS).

When I sat down to speak with Gloria Boutte and Jennifer Reed (CEEAAS Director), who launched the center last January in coalition with the College of Education, I started by contextualizing my own experience with the Corridor of Shame — as a participant in the historical phenomenon called “segregation academies,” or private schools (which previously had no place in South Carolina) that were founded between 1954 and 1975 to dodge the Brown v. Board of Education ruling. There’s half a century of racist precedent behind hundreds of private schools.

“It’s interesting that you use the word historical, because it’s symbolic of where the problem truly is. We don’t blame the students or the teachers. We look at education structurally in terms of things like funding, teacher preparation for rural or low-income areas, and the content of the curriculum itself,” said Boutte.

In my town — and really, across the state — a variety of excuses continue to rear their heads for why African American students rarely succeed to the level that white students do.

“This difference in achievement has existed since data first started being collected,” said Reed. “Over 50 years of disparity in equity and opportunity for black children. At a certain point, you might call it educational malpractice. How have we not yet managed to address the improvements necessary in this core group of children?”

“People used to refer to this issue as the ‘achievement gap,’ but we don’t like to use that term because it places blame on the student,” Boutte said. “Our programs are focused on outreach to future educators, as well as working hands-on in classrooms. The theme of our most recent conference was Culturally Relevant Pedagogy — Start Where You Are, But Don’t Stop There. Our Early Childhood Education program in the College of Education focuses on issues of equity. The goal is for educators to be prepared to address covert racism and situations caused by it in the classroom; we are here to give them those tools.”

They also addressed the concerning lack of teachers flowing into rural areas of South Carolina. “Our Apple Core Initiative hopes to start recruiting teachers out of high school, especially black teachers, as only 7 percent of teachers nationwide are black. That makes a difference in the classroom for young kids,” Reed said. “We are prepared to give them support through their years at USC and then three years into their first teaching position. Many people start teaching because they want to make a difference, but the reality of it is that teaching can be much more complex than that. We want to make sure that teachers feel that their concerns are being addressed.”

“When black children benefit, all children benefit,” said Boutte. “It doesn’t do anybody any good to have an inaccurate sense of history. Our motto is, ‘We believe in the power and the possibility of the Black child.’”

This article only can give so much space to the incredible work that the CEEAAS has been doing over the past year. I would encourage everyone, especially future teachers, to peruse their website, read through their pamphlets and ask yourself hard questions about how your educational privilege got you to where you are now. After all, only an educated public can start doing the work to revise and reimagine our state’s policies and values.