The girl on my Instagram never has a bad day.

She smiles with all her teeth and laughs with her mouth wide open. She never gets annoyed or frustrated because she has so much going for her. Her friends make her laugh. Her boyfriend makes her laugh. Her family makes her laugh.

The girl on my Instagram looks like me. Her blonde hair can’t decide if it’s wavy or straight and neither can mine. Her glasses are pretty big on her face and so are mine. She has a little mole on her right cheek, just like mine.

The girl on my Instagram is accomplished and quirky and looks like a good time, all of which are validated by the comments from her followers.

There’s no reason for her to be anything but elated.

The girl on my Instagram is me, but she doesn’t tell the whole story. It’s me in those pictures, smiling with all my teeth and laughing with my mouth wide open. But those are pictures from my highest days when I laugh the most and smile the widest. You won’t find pictures from my lows.

The girl on my Instagram never stays in bed all day because she feels like she can’t get up. She doesn’t cancel plans because she feels too low. She never cries for no reason.

But I do.

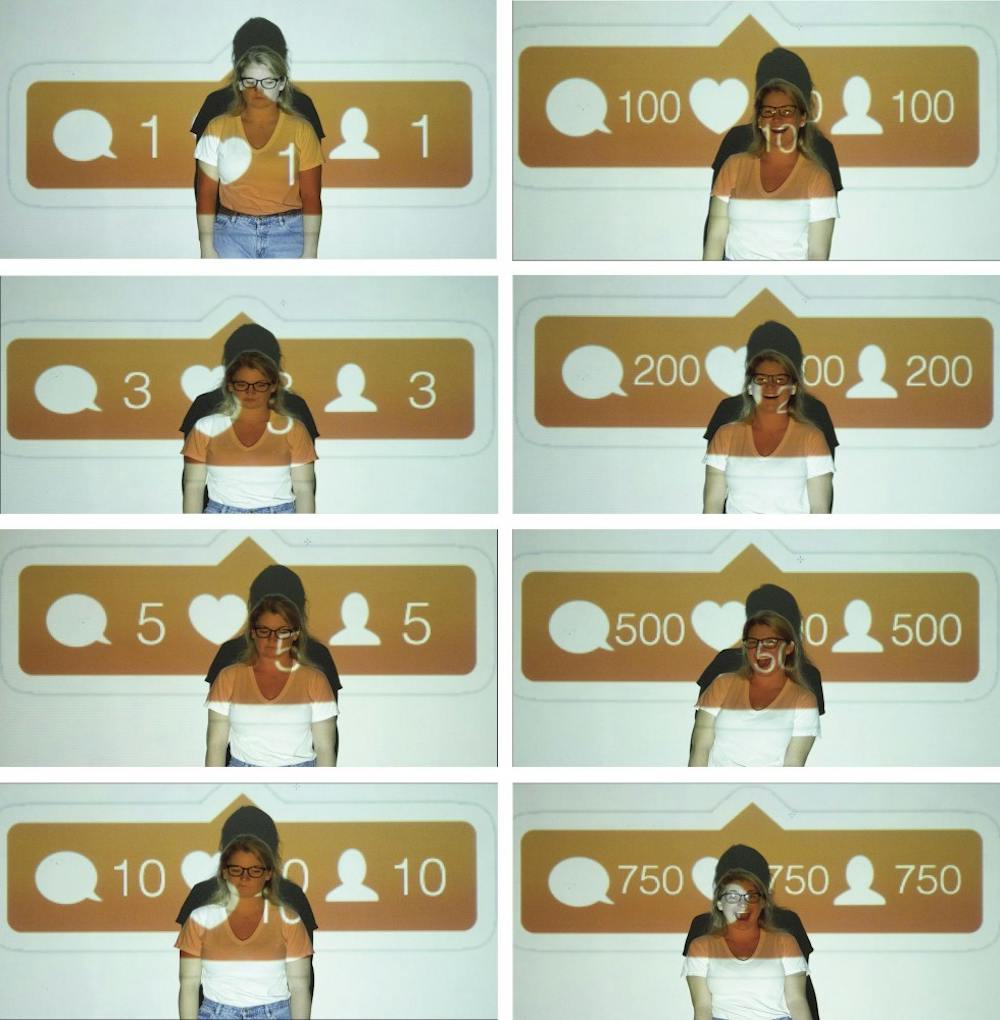

The girl on my Instagram and I have a lot in common, but she’s the one who gets the likes. My followers are double-tapping the idea that I’m always beaming and funny.

It’s not me they’re liking — it’s what I’m showing them.

Why have I created this profile of a person who is only part of me? When did I make the conscious decision to hide the rest of myself from everyone else? Why do I scrutinize over pictures of myself and mess with filters and try out three or four captions before I hit that publish button, only to show people pictures that only tell half my story?

I do it because no one’s going to like a picture of my puffy, tear-streaked face crying into my pillow with a caption that reads, “Things will never get better.” No one’s going to like how I’m really feeling because they want to see the happy girl they’re used to seeing smiling and laughing.

I want everyone else to see how much fun I’m having. Or, at least, how much fun it looks like I’m having.

I want people to think I’m happy, even if I’m not.

Generation Y is the first to deal with this social media anxiety phenomenon to this extent. We grew up with AIM. We were some of the youngest users on MySpace and Facebook. We were among the first to get Twitters and Instagrams.

College students today have more exposure to social media than ever before.

Dr. Rhea Merck teaches psychology at USC, and she battles smartphones every day in the classroom. While she’s at the front of the room talking about the brain, her students have theirs focused on their phones.

“There is so much more information that we have coming at us now, and our sympathetic nervous system tends to be more overwhelmed on a day-to-day basis,” Merck says. “And so, when we’re over-stimulated like that, it increases the likelihood that we could have anxiety as a reaction to it.”

That makes sense, given that today’s students have the highest rates of anxiety in college kids to date.

Earlier this year, the New York Times reported that anxiety is the No. 1 mental health diagnosis on college campuses. The Center for Collegiate Mental Health’s 2014 report put anxiety as the most reported reason for students seeking counseling. Out of 25,475 students from 140 collegiate counseling centers, 55.1 percent said anxiety was a concern. And 19.6 percent said anxiety was what concerned them more than anything else.

So, it’s not surprising that Toby Lovell, assistant director of community-based services for USC’s Counseling and Psychiatry center, says student anxiety is the No. 1 thing counselors at USC handle, too.

Anxiety stems from any number of sources: finishing homework; planning for the future; overthinking plans. Not to mention comparison — the idea that you aren’t doing as well as everyone else can make you feel doomed.

“I think there’s a false perception of ‘I am not as good as this other person who seems to have so much going for them in their life based on their Facebook posts,’” Lovell says. “We don’t actually know what’s going on personally in someone’s life. Just because someone’s posting positively on Facebook doesn’t mean they don’t have problems or concerns.”

But from freshmen in their first semester to seniors in their last, that’s hard to swallow. We spend so much time creating, tending to and checking our profiles, and even more time looking at everyone else’s. We try to make ourselves look like we’re doing so much, but it’s those who log off who are actually doing more.

The Higher Education Research Institute at UCLA’s “The American Freshman” report last year found that college students’ social priorities are changing — 30 years ago, students put emphasis on face-to-face time with friends. But now:

“At the same time that students report spending less time socializing with friends and partying, they are increasing interactions through online social networks.”

These days we see our friends on Instagram more than we see them on Friday nights. We’re spending more time crafting captions and tweets than we are out in the world with people because that’s what our friends are doing.

“And now [followers] have certain expectations for you, so there’s more pressure to live up to some social expectation,” Merck says. “So, what if you go off the radar and you become overwhelmed with anxiety and obligations and you don’t tweet for a while. Then what happens?”

That’s true. I have far more people checking in on my Facebook than I do checking in on me.

Social media is our generation’s crutch. We whip out our phones when we’re in the elevator with other people or in line at the store. We busy ourselves with old tweets and photos and statuses, so we don’t have to interact with people.

We provide our own distractions.

“But how can you get to know yourself if you’re always distracting yourself from yourself?” Merck says.

And that freaks me out. Because the answer is, I don’t know myself. I have two people to keep track of — me and the me I’ve created. I distract myself from my daily anxieties with this alter ego. I make the me I’ve created look desirable and popular and like someone everyone would want to befriend instead of going out and trying to be that person.

It’s a big cycle. We use social media to distract us from the anxiety we create on social media. We check Twitter instead of listening to lectures and then stress about poor grades. We feel a moment of satisfaction when scores of people like our pictures on Instagram but feel snubbed when no one asks us to hang out.

Coping mechanisms can help with anxiety and Lovell says the counseling center is happy to teach them. Merck wonders if it’s going to take a cultural or social crisis to break us of these habits. Hundreds of studies show us that anxiety rises year after year, and college students are already vulnerable.

Sometimes I think about how with one click, I could delete each façade I’ve created on Instagram and Twitter and Facebook. I could force people to know me, to know the whole story. I think about how much time I’d have if I stopped putting so much effort into concealing myself.

It would be so easy.

But I won’t do it.

I won’t do it because I like getting likes. I want that little orange bubble to pop up when I open Instagram and the little blue one on Twitter and the little red one on Facebook. I want people to like what I’m doing and saying and posting because for a brief moment I feel better.

For a brief moment, I feel like I really am the girl on my Instagram.